Flight

How girls of color flee from violence to violence

How girls of color fleeing violence are caught in the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline.

Come on an interactive journey across a systems map of modern-day slavery in the U.S. through a series of illustrated stories, videos, and maps of the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline.

Content warning: This experience includes written and spoken descriptions of sexual and physical violence.

Meet Alicia.

Alicia has been arrested for solicitation, drug possession, possessing drug paraphernalia, burglary, and parole violations. But that’s only part of her story.

Before she was labeled a “criminal,” she was a victim, a victim of sexual abuse.

When Alicia was twelve years old, she was raped by a classmate.

Her classmate told their peers a different story, and she started being bullied at school.

Depressed and withdrawn, Alicia began skipping school, shoplifting, and using drugs to numb the pain.

Eventually, she dropped out of school, and her mother said she had to leave because she was a bad influence on her younger siblings.

So Alicia moved in with her dealer, not knowing he was also a “pimp,” or someone who coerces girls into sex trafficking.

Alicia was only thirteen when he started withholding drugs to coerce her into having sex with men for money.

He kept her locked in the house, often chained in the basement, and he would make what’s called “outbound” calls, where men would come to her, or she would be taken to a hotel.

A few years later, when he felt she was old enough to go out on the streets, Alicia started getting arrested for solicitation and passed to different sex traffickers.

All of her traffickers kept her dependent on drugs, so she ended up serving drug-related prison sentences.

Alicia was caught in a vicious cycle of abuse and incarceration.

Every time she was released from jail, it was because a trafficker bailed her out.

And when she got out of prison, someone would be waiting for her...

Sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline: The ways in which we criminalize girls who are victims of sexual abuse.

The facts are staggering: one in four American girls will experience some form of sexual violence by the age of 18…and in a perverse twist of justice, many girls who experience sexual abuse are routed into the juvenile justice system because of their victimization. Indeed, sexual abuse is one of the primary predictors of girls' entry into the juvenile justice system…Once inside, girls encounter a system that is often ill-equipped to identify and treat the violence and trauma that lie at the root of victimized girls' arrests…This is the girls' sexual abuse to prison pipeline.

Flee

Where we depart

The sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline disproportionately harms Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) women and girls because attitudes and stereotypes about BIPOC women and girls create an environment where we are more vulnerable to sexual violence but less likely to be seen as victims.

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, and People of Color

Women and Girls: All woman-identified persons

"The vast majority of women in prison—85 percent to 90 percent—have a history of being victims of violence prior to their incarceration, including domestic violence, rape, sexual assault, and child abuse…[G]irls of color who are victims of abuse are more likely to be processed by the criminal justice system and labeled as offenders than white girls, who have a better chance of being treated as victims and referred to child welfare and mental health systems."

Meet Anne.

Anne's childhood was marked by parental abuse, so she spent as much time as she could away from home.

At just 13 years old, she was pursued by an older man who showered her with gifts and attention.

One night, as they headed to a party, the man offered her what she thought was marijuana - but it turned out to be laced with crack.

When her parents discovered her drug use, they kicked her out of the house.

Alone and exposed to the bitter cold, Anne turned to the older man, believing him to be her boyfriend.

She thought she had found a safe haven when he started introducing her to friends of his and intimidating her into having sex with them.

Isolated with nowhere else to turn, Anne found herself coerced into commercial sex under the guise of a supposed relationship.

Because she chose to stay with her boyfriend, she thought it was her fault when she was arrested for prostitution months later.

Anne believed she had brought it upon herself, unaware that the coercive forces at play were common methods of sex trafficking.

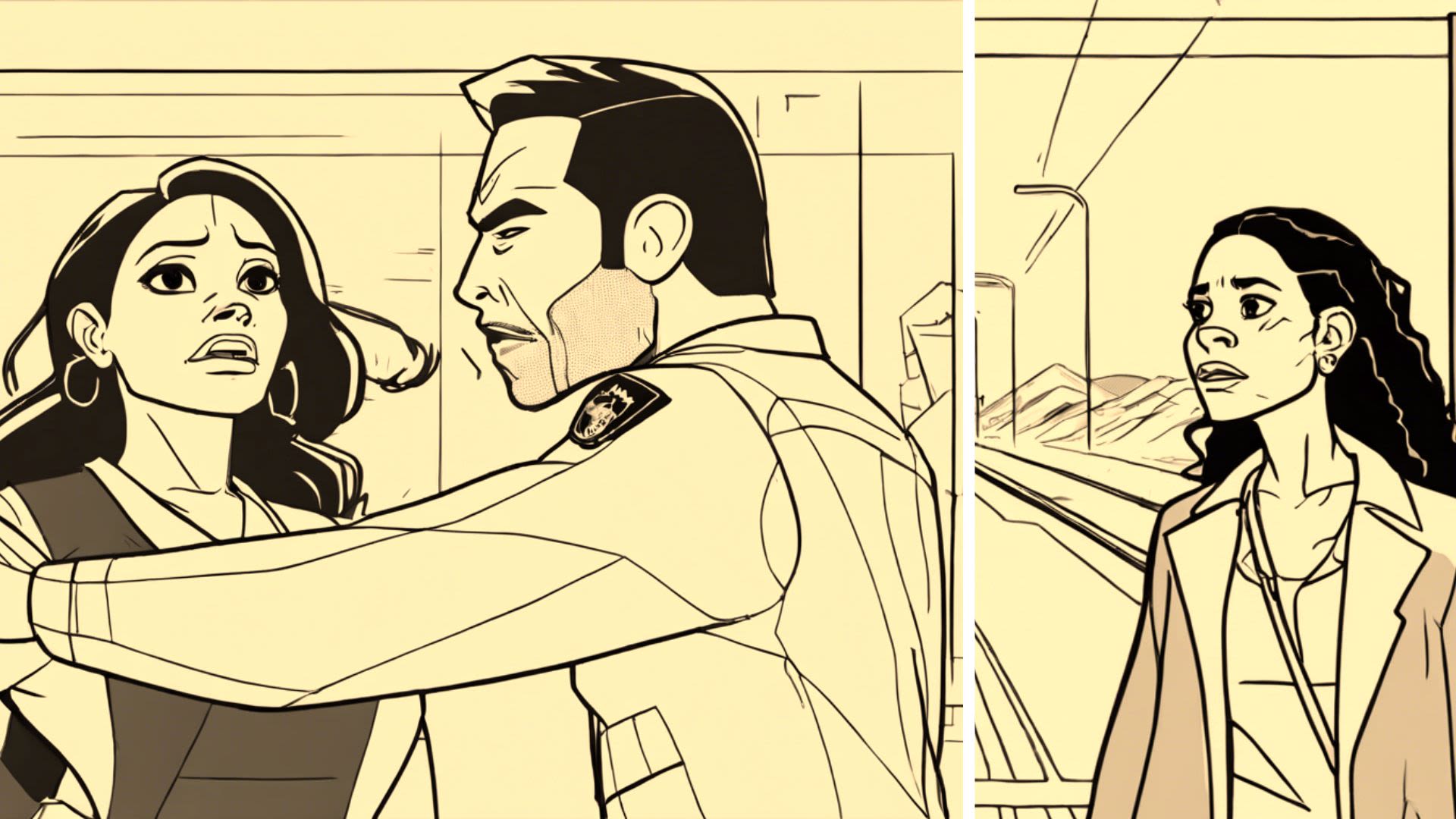

Domestic sex trafficking is an injustice that happens in plain sight. Many sex trafficking victims get arrested dozens of times. Common arrests include drug possession, truancy, possessing a fake ID, prostitution, and solicitation, even among minors. Charging a child with "minor prostitution" was outlawed in 2012 because minors are not of age to give consent. Still, many law enforcement officials don't know that and continue arresting and charging minors for solicitation and prostitution.

Female immigrants, who are often fleeing domestic and sexual violence, are exploited through sexual coercion or forced labor.

"For migrating women, this included being held captive and made to work in cooking, cleaning, or the commercial sex industry. It also included situations of debt bondage, or being made to work until a debt, which continues to rise arbitrarily, is paid off, in addition to other forms of exploitation, such as unpaid work."

Meet Aquene.

By the time Aquene was a teen, she was being molested by her stepfather, and her mother did nothing to stop the abuse.

After one especially horrific assault, she decided to run away.

While living on the streets, she met a man in his 60s who said she could stay at his home as long as she went to school. That requirement made Aquene think he cared about her.

She chose to stay with him, which was nice at first. But soon, he insisted that she contribute to the household by selling drugs.

She had two choices: go home and get molested or stay and sell drugs after school.

So she stayed with him and began selling drugs on the corner of her neighborhood until she was picked up by police.

When she was arrested for selling drugs, she never thought to tell the police anything was wrong because she felt it was her choice.

The sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline can take many different routes, considering the many ways victims can respond to abuse. Cries for help are often misinterpreted among BIPOC girls and responded to with criminalization. Girls could begin numbing their emotions with drugs, getting into fights, or engaging in high-risk sex behaviors. Those behaviors signal self-blame, maladaptive coping, and rape trauma syndrome and should be responded to with support services, such as counseling.

When the signs are missed, victims who flee interpersonal violence become victims of state violence.

Among women in jails, 86% have experienced sexual violence.

67% of women sent to prison in NYS in 2005 for killing someone close to them were abused by the victim of their crime.

Meet Ana.

When Ana and her eleven-year-old daughter were walking home one day, gang members stopped them and asked her daughter to turn around for them because she was pretty.

Ana had heard stories about gang members raping girls in her neighborhood in Honduras, and the police did nothing to stop them.

Fearing the worse, she decided to escape to the United States to protect her from what she felt was inevitable rape.

But when they arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, border police separated her from her daughter.

Ana was placed in a detention center to await processing of her asylum claim.

Between 2015 and 2018, the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies has aided attorneys representing asylum seekers in more than 7,500 cases of women and girls from the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Of those, 56% involved domestic violence, and 35% involved sexual violence and other forms of gender-based persecution.

"Asylum applicants receiving legal assistance from our organizations include those who have faced repeated incidents and multiple forms of GBV, often at the hands of family members, criminal gangs, state actors, or a combination thereof. For example, one woman from Mexico, a childhood survivor of abuse by her father, was kidnapped at age 13 and abused by her captor. She was later trafficked into forced sex work, and one of her "clients" included a local police officer."

"Women described a wide array of violence over the course of time, beginning with the motivation and preparation to migrate to their present lives in the United States. These experiences occurred before, during, and after migration and coalesced around five major, interrelated categories—domestic violence, sexual violence, human trafficking, gang violence, and state violence—at the hands of intimate partners, loved ones, new acquaintances, strangers, and government officials. Women did not talk about these experiences with violence along a continuum, which may presume rank order. Rather, these were complex acts of violence that were peppered and intertwined throughout their migration journeys—constellations of violence."

Origins

How did we get here?

Modern-day slavery refers to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because of threats, violence, coercion, or deception.

Chattel slavery was slavery based on belonging to a category, as in race-based slavery in antebellum America.

Forms of modern-day slavery:

- forced labor

- forced marriage

- debt bondage

- commercial sexual exploitation

- human trafficking, including sex, labor, and organ trafficking

- and any sale or exploitation of children

“In all its forms, it is the removal of a person’s freedom — their freedom to accept or refuse a job, their freedom to leave one employer for another, or their freedom to decide if, when, and whom to marry — in order to exploit them for personal or financial gain.”

Modern-day slavery is interwoven into socioeconomics in the U.S. through the prison industrial complex, which consists of prisons, jails, detention centers, and vast supporting apparatus. It costs the government and families of incarcerated people at least $182 billion every year, with almost half of the funds going to pay government staff.

In addition to public profits, there are over 4,100 companies linked to the prison industrial complex in the U.S., amounting to over $80 billion. The scope of the prison industrial complex, combined with the estimated $32 billion from human trafficking, makes modern-day slavery a major U.S. industry.

As a society, we are comfortable seeing BIPOC folks incarcerated. We are very uncomfortable confronting our history and ongoing legacy of chattel slavery. Chattel slavery was dehumanizing. The prison industrial complex dehumanizes folks by labeling them criminals. Then, it’s easier to violate their human rights and subject them to cruelty.

How does the legacy of slavery in America show up in the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline?

Map

Finding Direction

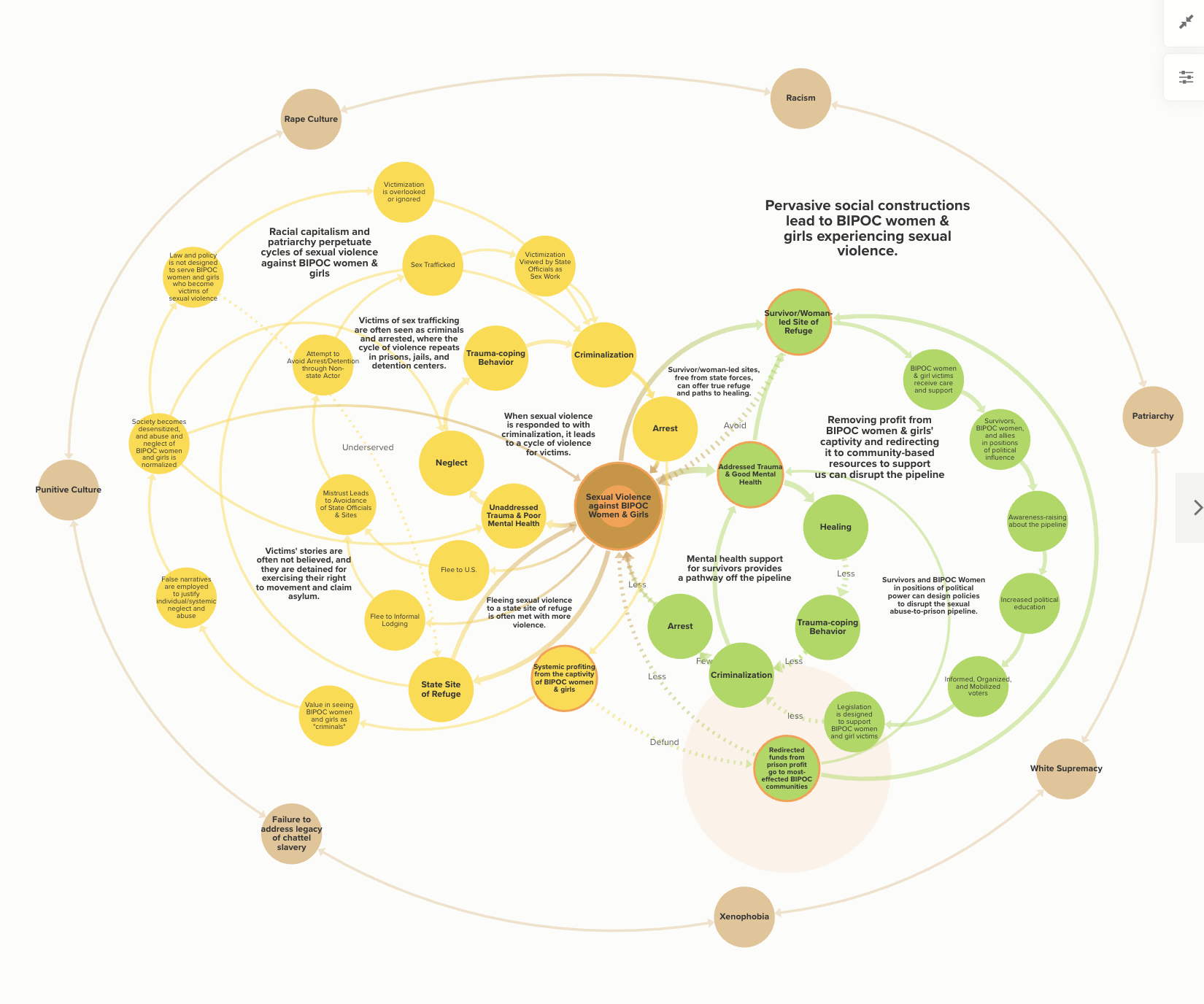

The systemic criminalization of BIPOC women and girls who are victims of sexual abuse is a major driver of modern-day slavery in the U.S. and constitutes a serious human rights issue. Historical analyses provide a linear understanding of how systems create unjust impacts. A systems map is a better tool for illustrating how complex systems of modern-day slavery operate in concert with the prison industrial complex.

Systems mapping is a visual tool that looks at how components interact and form patterns across the system, identifying gaps and opportunities for improvement. It’s powerful in social movement work, where collective actions from multiple stakeholders are required to change an unjust system.

By framing human trafficking, incarceration, and immigrant detention as one problem of modern-day slavery, a systems map fills a need for an intersectional approach to understanding and responding to cycles of violence.

To learn how best to interrupt cycles of violence, a team of a dozen participatory action research partners gathered to create a systems map based on real stories of BIPOC women and girl victims and survivors of the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline in the United States.

Participatory action research partners included folks directly impacted by incarceration, detention, and sex trafficking, as well as those working in the fields of reentry and other social services, higher education in prison, academia, and direct action organizing.

How do we disrupt BIPOC women and girls being hyper-visible as criminals while our victimization is invisible?

With that question in mind, we shared stories of witnessing the pipeline, conducted interviews, and collected research. We compiled reports of BIPOC women and girls who were victims of sexual violence and were punished with incarceration or detention to draw our map.

The result is this systems map of the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline for BIPOC women and girls in the U.S.

Note: This is an interactive systems map. Use the + and - buttons on the right to zoom in and out and learn about the different elements. Hover on a circle to see the elements that connect with it. Hover over a sentence description to view all the elements connected to that particular loop. And refer to the legend in the bottom left corner to understand the many pathways along this system.

Reroute

How do we change course?

By listening to the stories of BIPOC victim-survivors, we found 10 common journeys that resonated across all forms of modern-day slavery in the U.S. Understand the forces that create the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline by following the aggregate journeys of victims and survivors of modern-day slavery in the U.S.

1. When sexual violence is responded to with criminalization, it leads to a cycle of violence for victims.

2.

Victims' stories are often not believed, and they are detained for exercising their right to movement and claim asylum.

3.

Victims of sex trafficking are often seen as criminals and arrested, and the cycle of violence repeats in prisons, jails, and detention centers.

4.

Fleeing sexual violence to a state site of refuge is often met with more violence.

5.

Survivor/woman-led sites, free from state forces, can offer true refuge and paths to healing.

6.

Mental health support for survivors provides a pathway off of the pipeline.

7.

Survivors and BIPOC Women in positions of political power can design policies to disrupt the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline.

8.

Racial capitalism and patriarchy perpetuate cycles of sexual violence against BIPOC women & girls.

9.

Removing profit from BIPOC women & girls' captivity and redirecting it to community-based resources to support us can disrupt the pipeline.

10.

Pervasive social constructions lead to BIPOC women & girls experiencing sexual violence.

Modern-day slavery reflects the opportunity gap in America. The more precarious your status or position is, the more at risk you are to be trafficked, incarcerated, or detained. Those persons are overwhelmingly Black, Indigenous, and girls of color.

For many BIPOC women and girls, the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline reflects several system failings. Systemic failings work with the prison industrial complex to present us with few safe options but several bad ones, often leading to prison.

As stated earlier, the U.S. has a long history of profiting from forced labor dating back to 1619 with chattel slavery. Seminal works such as Angela Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete?, Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag, and Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow offer analyses of how the U.S. has been replacing the profits lost from the abolition of chattel slavery through hyper-surveillance, criminalization and incarceration of BIPOC. Their research provides a basis for viewing the prison industrial complex not as a broken system but as a carefully designed web of laws and policies intended to maintain the status quo.

The profits made from human captivity disproportionately exploit BIPOC women and girls who are overrepresented in every form of modern-day slavery but underrepresented in service provision, funding, and positions of political power.

Participatory Action Research Partners analyzed the map to discover opportunities for systems change and made a critical observation:

There are mirrored cycles that advance the pipeline and cycles that interrupt it.

In order to change the course of the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline, we must address supply and demand, the victims of sexual violence, and the sources of sexual violence. In other words, the systemic profiting off of BIPOC women and girls caught in forms of modern-day slavery must end and be replaced with investments in healing for survivors and transforming communities into spaces where we can thrive.

Stop the flow of the pipeline by defunding private prisons and other sources of profit from the captivity of BIPOC women and girls and redirect funds to community-based resources that support survivors of sexual violence and prevent new harm.

Funds would be better spent to build systems that center on healing, restorative, and transformative practices as they directly relate to BIPOC women and girls impacted by sexual violence and the prison industrial complex. Mental health support for survivors also provides a pathway off of the pipeline. And survivor/woman-led sites, free from state forces, can offer true refuge and paths to healing.

Soar

Rising above the current system

As a society, we can rise above our current system that produces the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline by implementing these strategies:

Defund-Fund & Divest-Invest

We can change the direction of the flow of money through collective action to divest and divert funds away from the prison industrial complex and towards resources and spaces for radical healing.

Undo Miseducation & Re-educate

Challenge patriarchy through education, beginning in kindergarten, bringing up a new generation that creates a culture of consent. Promote youth education and de-stigmatization around sexual violence.

Shift Visibility & Invisibility

We can’t name what we can’t see. Invisibility is powerful, so we need to know where and to whom prison profits go. Create public accountability for those who profit from BIPOC girls’ captivity by removing their invisibility and learning to be active bystanders to disrupt the normalization of seeing BIPOC women and girls experiencing violence.

Change the Narrative & Norms

“The school-to-prison pipeline” is an issue that centers on boys’ experiences in school rather than girls. “The sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline” better explains girls’ experiences. Make the shift to centering girls’ experiences and challenge the norm of domestic violence and patriarchal violence as unavoidable societal problems.

Join the Abolition Project in collective and individual strategic action to combat the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline for BIPOC women and girls.

Support organizations addressing the sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline and equip yourself to respond to sexual violence.

- ASISTA: For resources specific to immigrant victims and survivors of gender-based violence, visit https://asistahelp.org.

- Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women https://www.csvanw.org

- Critical Resistance https://criticalresistance.org

- National Black Women’s Justice Institute https://www.nbwji.org

- The National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project https://niwaplibrary.wcl.american.edu

- Survived and Punished https://survivedandpunished.org

- VAWnet: For a directory of resources on preventing and responding to violence against women, visit https://vawnet.org.

For immediate support, refer to the following helplines that respond to incidences of violence against women.

- National Sexual Assault Hotline: If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, call 800-656-4673 for confidential 24/7 support or chat online at online.rainn.org.

- National Human Trafficking Hotline: If you think someone is a victim of human trafficking, call 1-888-373-7888 or text 233733.

- Refugee Women’s Alliance (ReWA): A helpline for immigrant and refugee victims of domestic violence or sexual assault is Peace in the Home Helpline: 1(888) 847-7205 or visit https://www.rewa.org.

- Hearts Native Helpline: For domestic and sexual violence help for Native Americans and Alaska Natives, call 1-844-7NATIVE (762-8483) or visit https://strongheartshelpline.org.

Thank you for taking a journey through Flight

The Abolition Project is a think-and-do tank dedicated to abolishing all forms of modern-day slavery.

Sign up for the mailing list and follow on social media to stay informed of new developments with the Abolition Project.

Consider donating to support this free content and future Abolition Projects.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by a grant from Voqal Partners.

I want to give special thanks to all the participatory action research partners who contributed their experiences and expertise to building the systems map used in this story.

This story is in tribute to my Aunt Shirlene and to all of the girls whose victimization went unseen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.